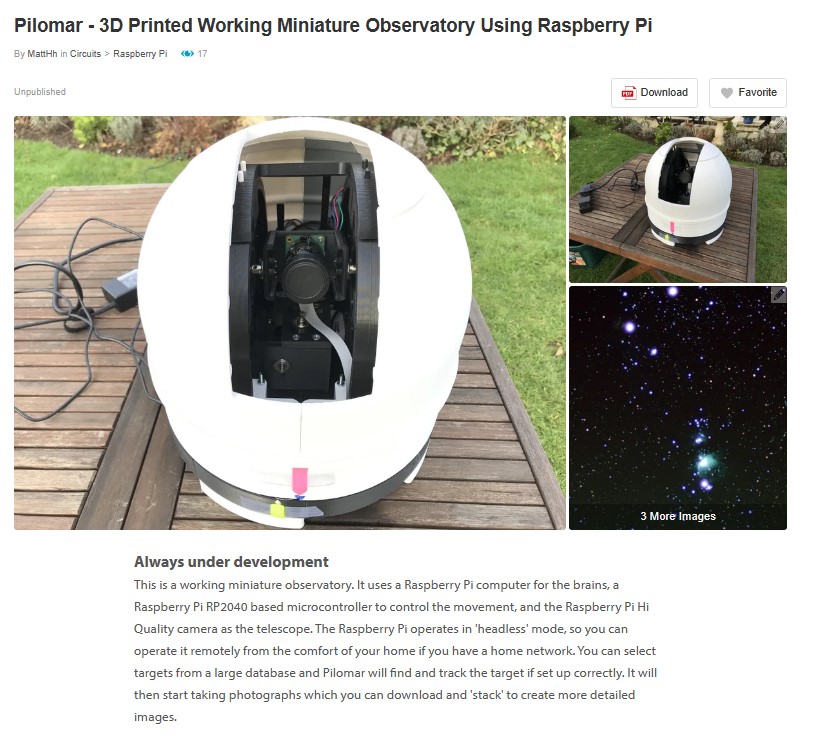

Testing Pi-lomar on the Raspberry Pi 5

Will Pi-lomar run on a Raspberry Pi 5?

Spoiler alert! No.

Not yet.

The camera and GPIO libraries have changed, but how close is it to working?

Interestingly more of the required packages that made the RPi 4 Buster build tricky seem to be pre-installed in Bookworm now. I only added opencv, astroalign, pandas and skyfield, and they all installed cleanly, no conflicts or special tricks needed.

sudo apt install python3-skyfield

sudo apt install python3-opencv

sudo apt install python3-astroalign

sudo apt install python3-pandas

The resulting build script will be much simpler I hope. I’m still installing globally rather than creating containers because the RPi will be dedicated to the telescope.

The pilomar.py program of course errored out fairly quickly, but with relatively little change I got it up and running as far as the first menu. That includes all the data loading and formatting that has to happen when you first run the software.

Right out of the box I have to say “wow!“, I’m impressed.

For comparison: The 2GB RPi 4B with the 32bit operating system takes about an hour to calculate the Hipparcos catalogue of 100000+ stars. On an 8GB RPi 5B with 64bit operating system, it ran in 25 seconds, so fast that I thought it had failed, I had to speed up the progress messages to prove it was doing something. From nearly 60 minutes down to 25 seconds! In regular use I’d estimate Pi-lomar runs about twice as fast on the RPi5.

It looks like the basic migration should be straight forward, and there is capacity there for extra features.

Raspberry Pi 5 Active Cooling hint!

The official cooling unit is great – it’s very easy to attach to the RPi5. BUT – you can’t detach it. So, if you’re thinking of later putting it into a case or occasionally reorganize things, be very careful.

For example: I like the Pibow cases, but a couple of design choices clash. If you connect RPi+Cooler first: You cannot fit all the layers of the case.

If you connect RPi+Cooler second: You cannot remove all the layers of the case, and the camera connectors become more difficult to access.

Next time I’ll change the little spring-loaded feet for nylon bolts so the cooler can be removed – that’s the fundamental design flaw to me.

Back to the RPi 4B version

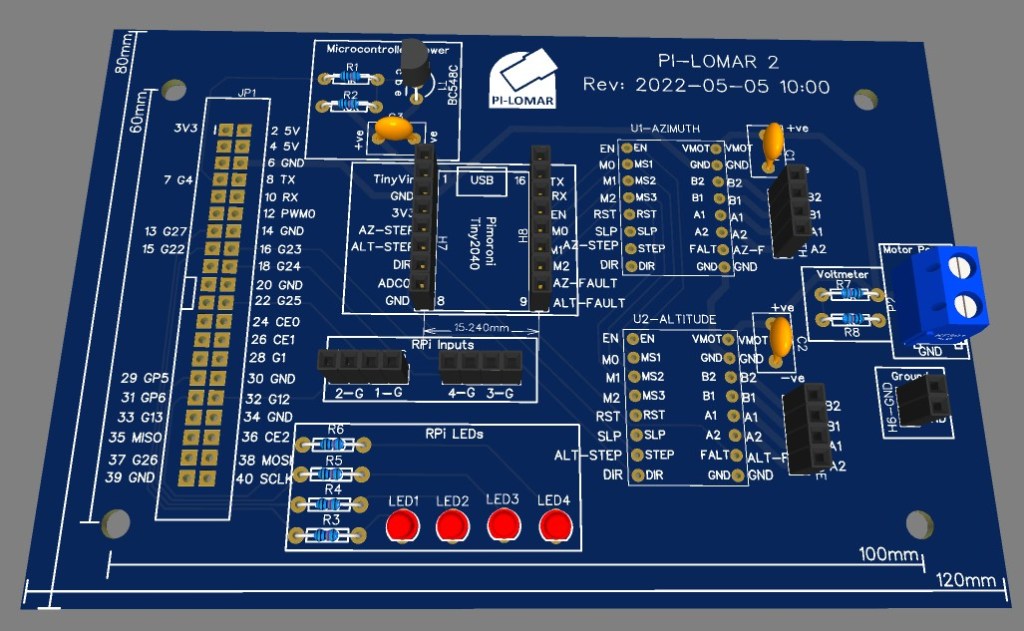

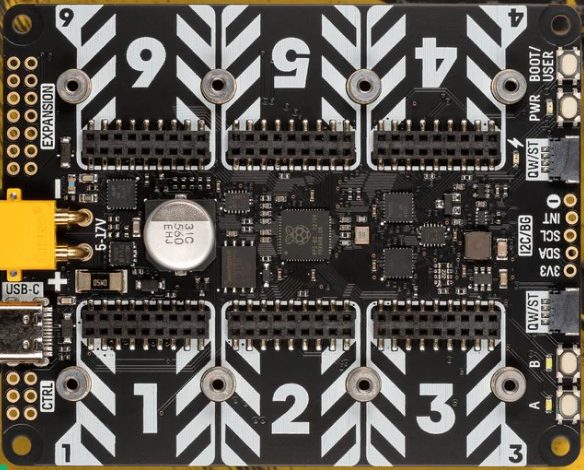

Motorcontroller PCB

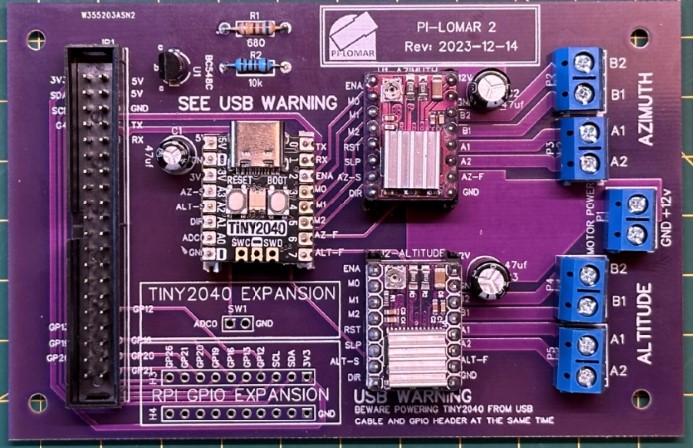

The first PCB design is done and the Gerber files are now in the GitHub project for the PCB. These files can be used to manufacture the PCB. It still needs to have components added, but the wiring is all set in the PCB itself. Many thanks to Dale, Mark, and Ton for their help with the designs so far.

The published PCB has a few improvements on it.

- Full ground plane on the underside of the PCB.

- 12V supplies have more copper too.

- The unused ADC0 pin on the Tiny2040 is now available in the expansion section for your own use.

- A number of GPIO pins from the RPi header are now exposed in the expansion section.

- Some development features (LED and motor power measurement) are removed.

- PCB connector blocks have been standardised.

- Printed warning to take care when connecting USB and GPIO at the same time.

- NOTE: On the published Gerber files, the ‘R1’ resistor is marked with a lower value than these images show. Any value from 320 – 680 Ohms seems to work fine. The lower the value, the better the transistor switches.

I have added a new folder to the GitHub project to contain the Gerber files.

https://github.com/Short-bus/pilomar/tree/main/gerber

The files for the PCB are in the /gerber/PCB-2023-12-14 folder on GitHub. You must generate a .zip file from here to use for manufacturing.

cd gerber/PCB-2023-12-14

zip PCB-2023-12-14.zip *

The PCB-2023-12-14.zip file is the one that you should submit for manufacturing.

The file gerber/readme.txt explains more about the manufacturing specifications you will need to provide when placing an order.

A second PCB design is still in testing at the moment, this one eliminates the separate Raspberry Pi power supply. It adds a buck converter onto the board to act as the RPi’s power source. Everything runs from the motor 12V supply.

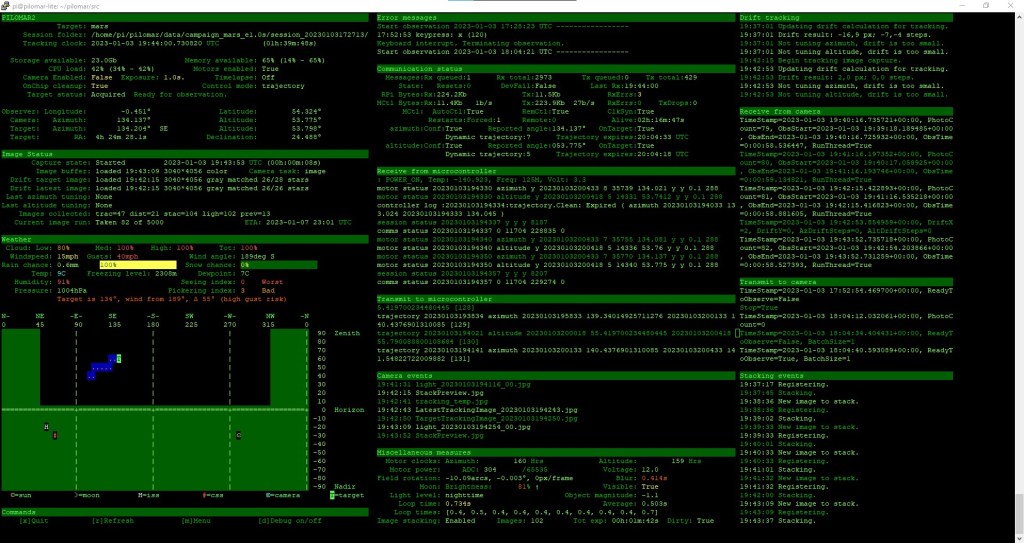

Software development

At the end of December I released a few improvements to the software, fixing a few issues that the early builders found. I think people should be taking their first images soon, so I’ve done a little more development in January to help tuning the telescope.

The tracking algorithm works for me, but I suspect that it needs finetuning to individual observing conditions. There are some great sounding locations where people are building Pi-lomar at the moment. So I’ve started adding some simple tools to help get the tracking parameters right. The idea is to show the results of the tracking calculation and the related parameters which can impact how it works. (I must explain how the tracking solution works soon)

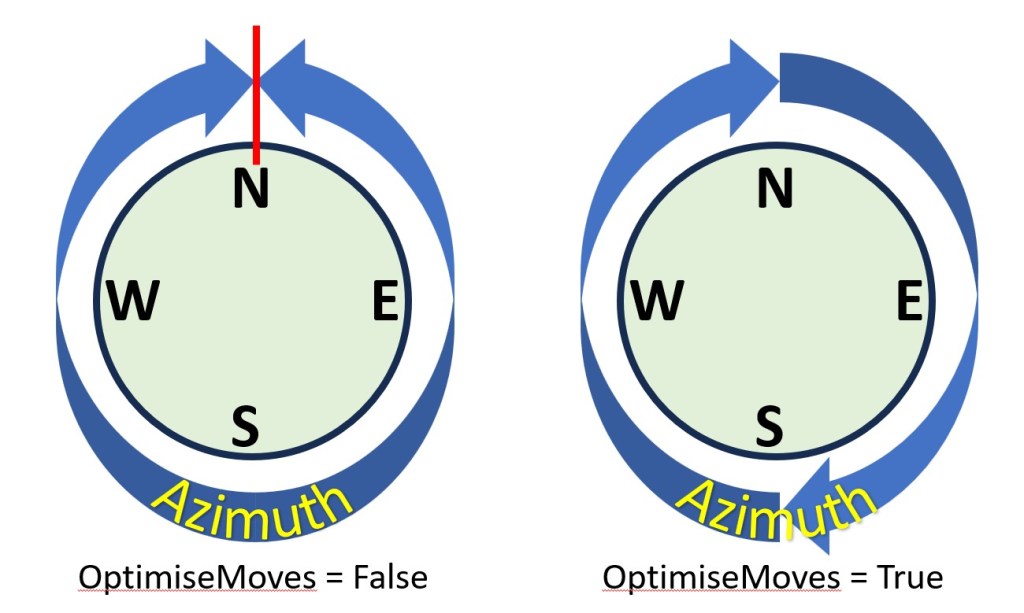

Getting the telescope working south of the Equator! I am at 50+ degrees North here, out of extreme caution I put a warning on Instructables and in the software that the telescope might not work if you go too far south. But there is interest to make copies in the Southern Hemisphere. So with help from volunteers I’m looking at addressing some minor irritations with how the telescope behaves as you move further south. It looks like Pi-lomar will work already – but with a movement reset while tracking objects through due North. So the January release will accept Southern latitudes for the home location now and just warn you that it’s still under development.

There’s now a parameter “OptimiseMoves” – when you turn that parameter on the telescope will move much more freely through due North which should eliminate some irritations.

I’ve opened discussions on the GitHub site for anyone who wants to join in. When the feature is fully developed and proven to work that will become the normal operation everywhere.

The January improvements will be merged back into the main branch in the next few days.

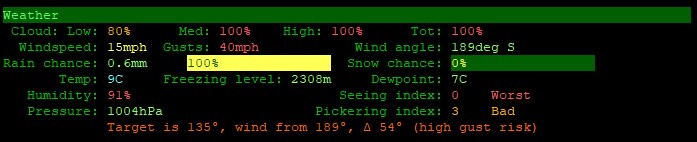

Actual observations

It has been almost constantly cloudy here for months now. And the back yard is turning to mud, even the dog is reluctant to go out there. Really frustrating! I’m SO desperate to get out and get some more images captured. Nights on the east coast seem to come in three flavours…

- Too cloudy, calm, no moon.

- Clear, too windy, no moon.

- Clear, calm, full moon.

I’m hoping that some of the other builders will start capturing soon, maybe people can share those images too.

Hardware developments

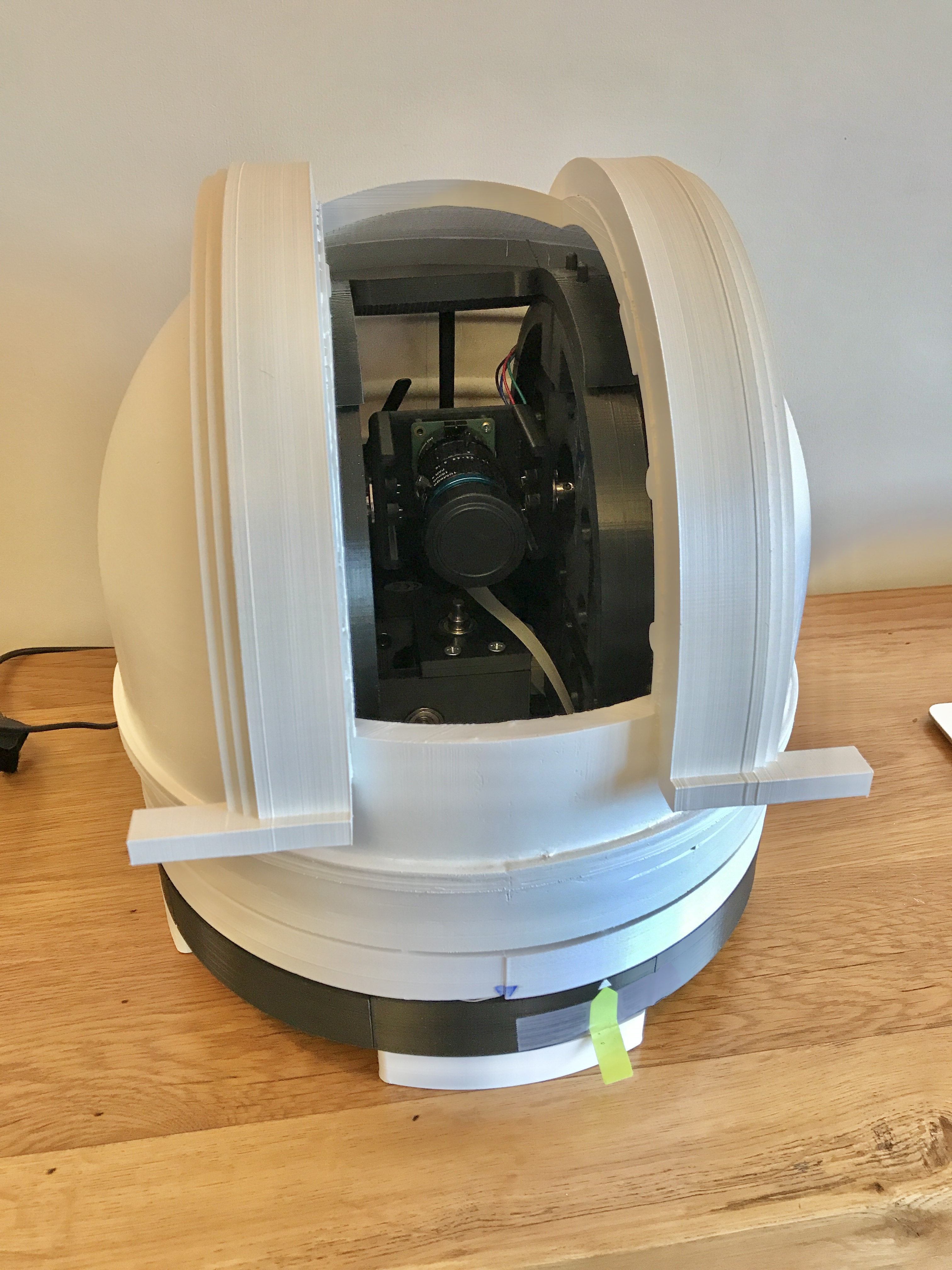

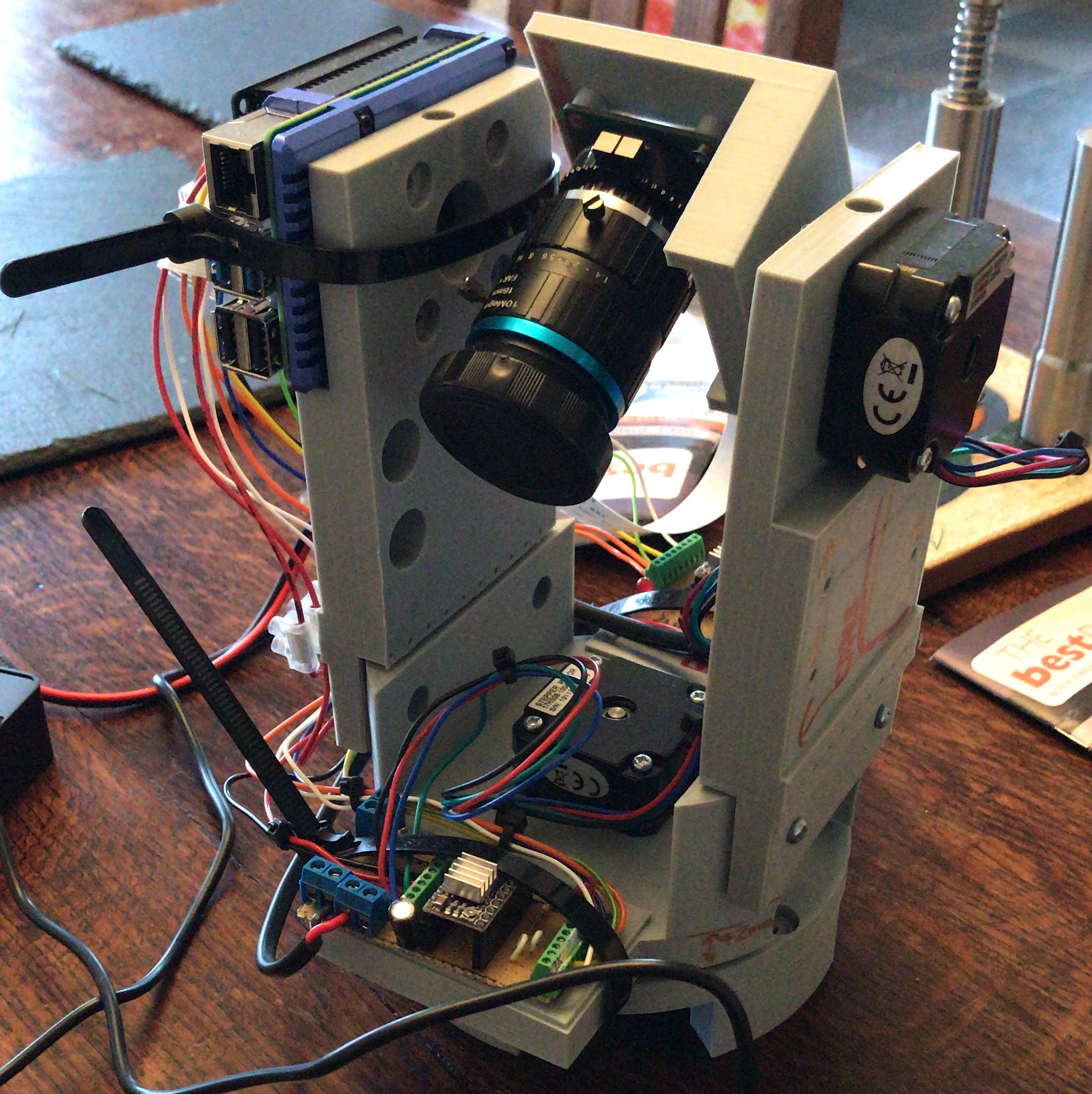

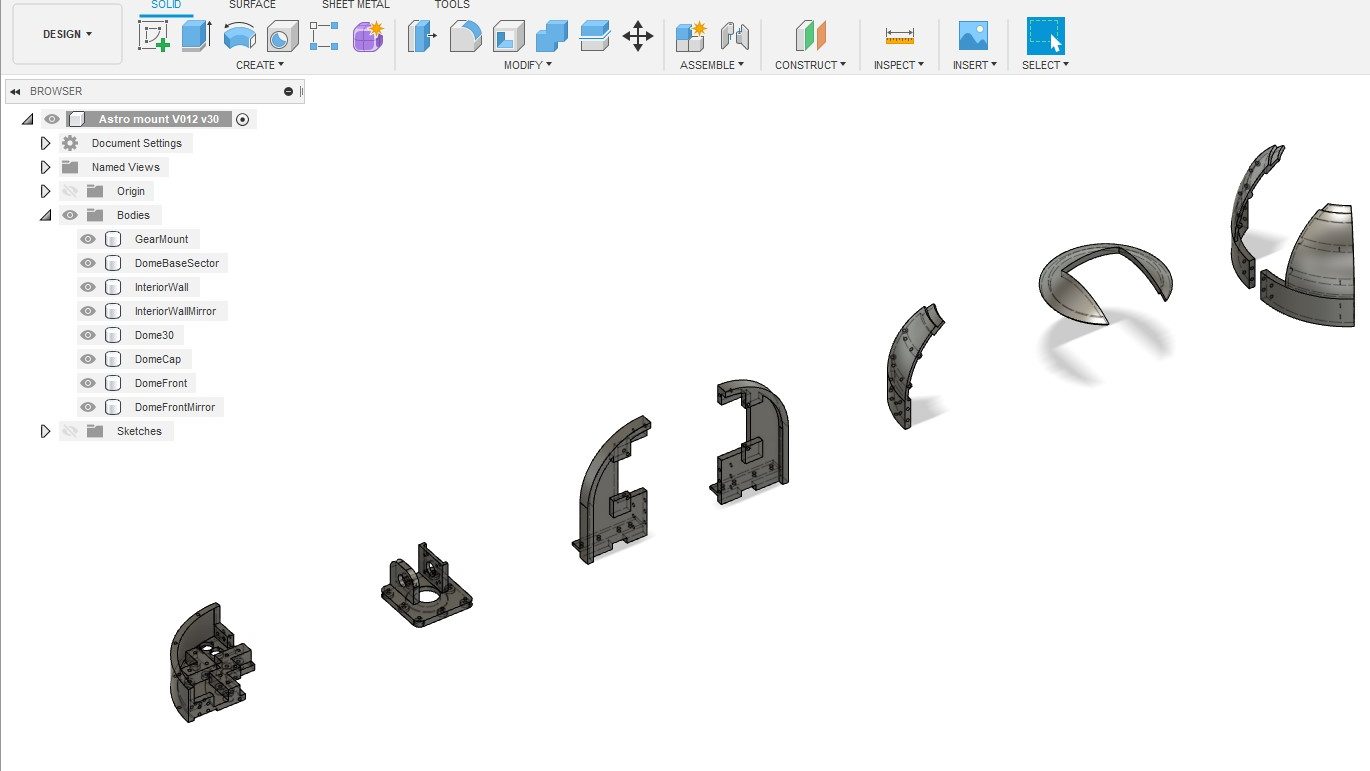

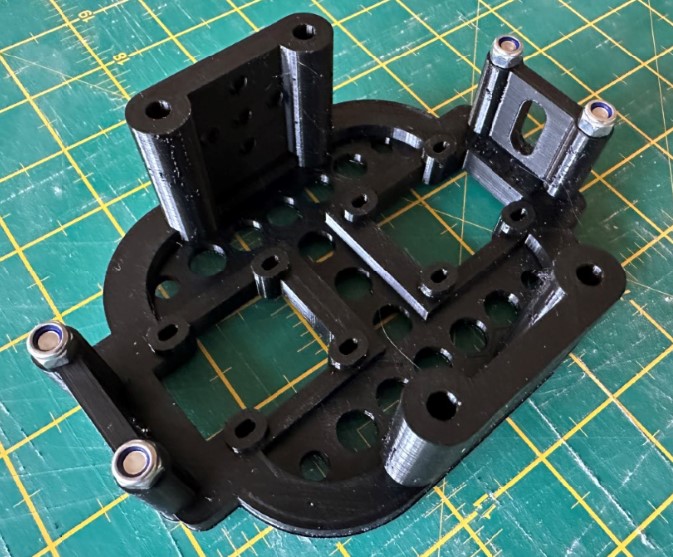

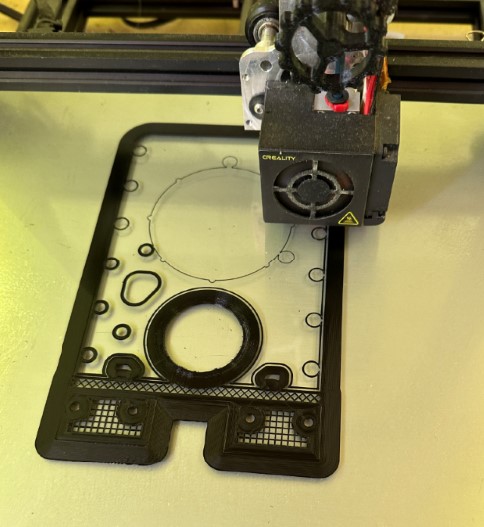

Upgrading mk1

I have two completed Pi-lomar telescopes at the moment. After a break from 3D printing, I’m returning to the earlier build to upgrade it. The drive mechanism now feel less smooth than the Instructables version. That’s a relief! All the tweaks I put into the Instructables version made a difference. So I’ll be tearing mk1 down and testing out some further improvements to the drive and telescope tower. I’ll take the opportunity to widen the camera cradle – it will allow more room for higher quality lenses, and also let me test out the idea of an RPi5 with twin cameras later this year.

Removing the infrared filter

Finally time to rip that infrared cut-off filter out of a Hi Quality sensor. The official instructions work, it is simple to do. The lens mount comes off the sensor board easily and the IR filter pops out cleanly with gentle push. I have left the sensor exposed, protected only when a lens is attached. I may try to re-cover it with OHP film as suggested as exposed sensors are dust magnets! I put the sensor inside a fresh clean freezer bag to minimise dust when making the mod.

I placed the 16mm telephoto lens on the sensor and stuck it on a tripod just to see what things looked like. Everything has now gone ‘pink’ so SOMETHING has changed anyway!

It’s not clear how wide the HiQ sensor’s infrared sensitivity is, but I think any expansion of wavelengths will be interesting to play with.

Fiddly focusing

I had to refocus the lens when I reattached it, and realised a better way to get it in focus. The focus ring of the 16mm lens is not very precise compared with larger lenses, I’ve always struggled a bit with this. I tried a different approach this time.

I set the lens focus ring fully to ‘FAR’ and locked it off. Then released the screw clamping the sensor mounted rear focus ring. That’s a much finer screw thread, it has a more positive movement, and allows really fine focus adjustment. It is mentioned in the official instructions, but I think it’s the BEST way to focus if you’re being fussy.

With this, the ‘raspistill –focus‘ command trick and some patience you can get quite fine control over the focus. You DO need a monitor connected via the HDMI port though. The preview image does not appear through VNC or puTTY sessions.

As always, it’s best to close the aperture ring a little to increase depth of field. I always reduce it to F2.8 so it’s still bright, you can reduce further if you are having problems.

Light pollution

We sit just outside an expanding town which is switching to LED streetlighting. Light pollution is an increasing problem. I have purchased a simple ‘light pollution‘ filter to add to the 50mm Nikkor lens. I will be testing this as conditions allow, I wonder if it helps, and I hope it doesn’t block infrared!

Other builds

As mentioned earlier, quite a few makes are now underway with the Instructables project. The first ‘I made this‘ post has appeared (well done Jeff!), and from the messages I have seen there are a few nearing completion.

It looks like the most common pain points have been the PCB (see above) and sourcing the motors and worm gear components. Hopefully PCB sourcing is easier now with the published Gerber files. I saw a couple of cases where people shared a PCB order to reduce costs.

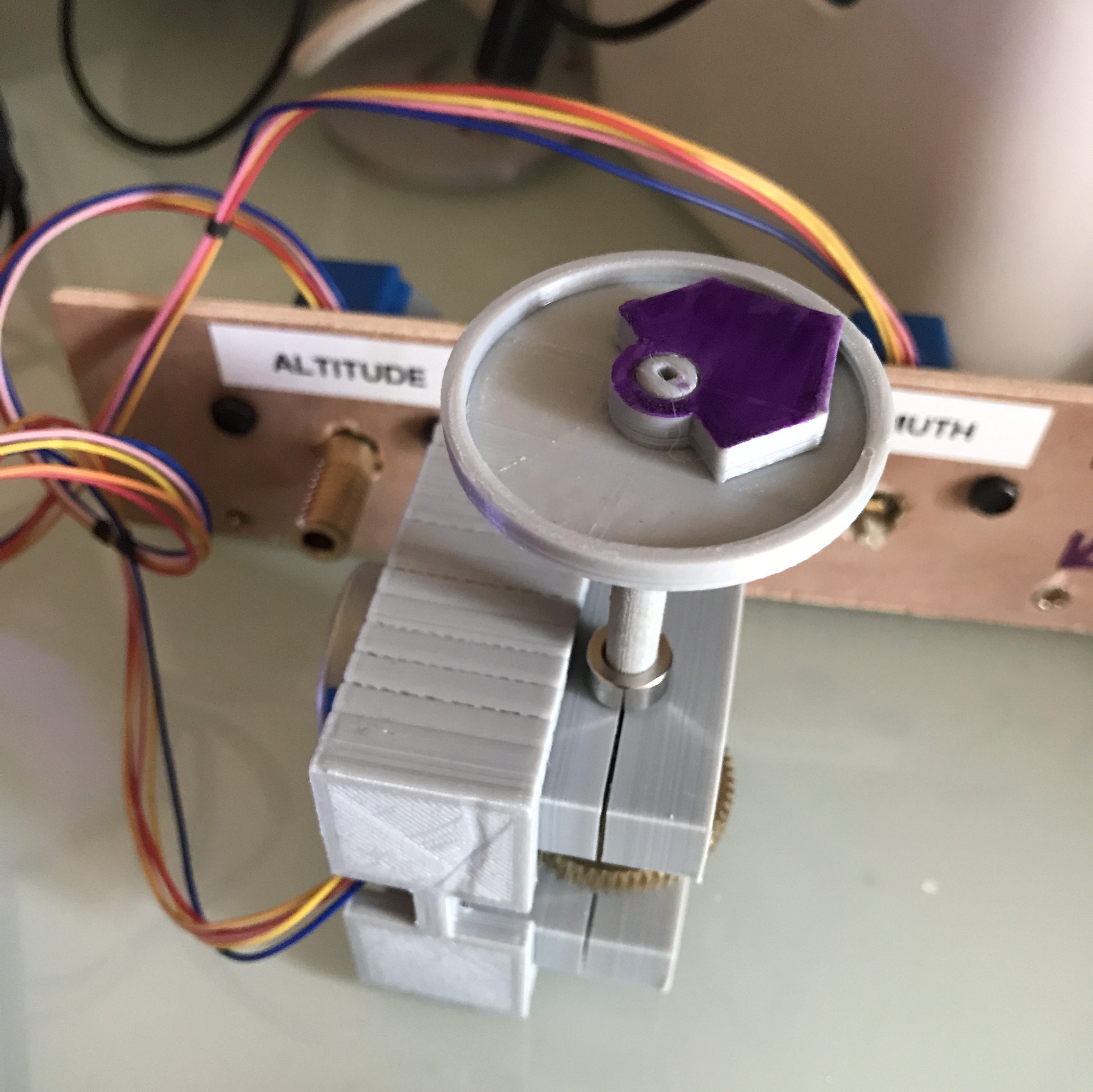

For the worm gear, I wonder if a future design could switch to using planetary gearboxes on the Nema17 motors instead. They seem to be more widely available, and can even be purchased as complete units. They may require a rethink of the drive mechanism, I have ideas already.

At least one builder is improving the weatherproofing of the design, that will be exciting to see when it is ready. I think there is a lot to learn from that development if it happens.

There are a couple of really interesting alternative motor controller designs out there too, including alternative ways to power/reset the Tiny2040 as well.

Off the shelf motorcontrollers

I mentioned in December that I haven’t found a suitable off-the-shelf motor controller board yet. Well, in the tech world, a month is a long time. I recently came across an announcement from Pimoroni about their new YUKON board. The specifications sound interesting. It supports high current stepper motor drivers, has a modular design and an onboard RP2040. There’s a fully featured builders kit available, but you can also buy the bare board and individual driver components. Pimoroni’s website has a couple of overview videos, and there’s an example robot project on Youtube by Kevin McAleer. I’d like to try one of these at some point, IF I find the time. Maybe someone else will give it a try?

So, quite a bit to test now. Here’s hoping for some clear, calm, dark skies before the winter is over!