Instructables builds

There are now 9 builds listed on the Instructables website, I’ve also had contact from other builders, I guess there are around 20 telescope builds out there. So there’s a small – but amazing – community forming for the telescope now. To create a sort of support group for the project I’ve created a Discord group for people who are building or running a copy of the telescope.

PM me via the Instructables project page for a link if you would like to join.

GitHub for pi-lomar updated

A large number of changes to the package are in the latest release just published on GitHub. There is a list of the changes, and some hints about upgrade options here.

The most significant changes in the new release are

Now runs on Raspberry Pi 5.

The GPIO handling is different on the RPi5, so I had to redevelop and retest the GPIO code to work there. This reinforces the advantages of switching to Bookworm 64bit O/S. The RPi4 and RPi5 both run pilomar happily on Bookworm now. Support for the RPi3B with the old ‘Buster’ build remains, but it cannot support some of the new features in this latest release. If you want to upgrade to the latest version I now strongly recommend a RPi4B or RPi5 as the main computer now.

FITS image handling.

With support from a few people in this project, and also from Arnaud and the Astrowl box project there’s now a way to save .fits format image files. FITS file formats are required by some astro image processing software. The raspistill and libcamera-still utilities will save raw images in .DNG format, but that is not accepted by some software. This new FITS format only works on Bookworm builds because it requires the picamera2 package to be available. You may be able to get this installed on earlier O/S versions, but I think it will need some tinkering. The FITS handling has been done by creating a new standalone Python routine (src/pilomarfits.py) which can be called just like the ‘libcamera-still’ command, but which generates .JPG and .FITS files instead. This is likely to improve further in the future, it’s just an initial attempt to add FITS format.

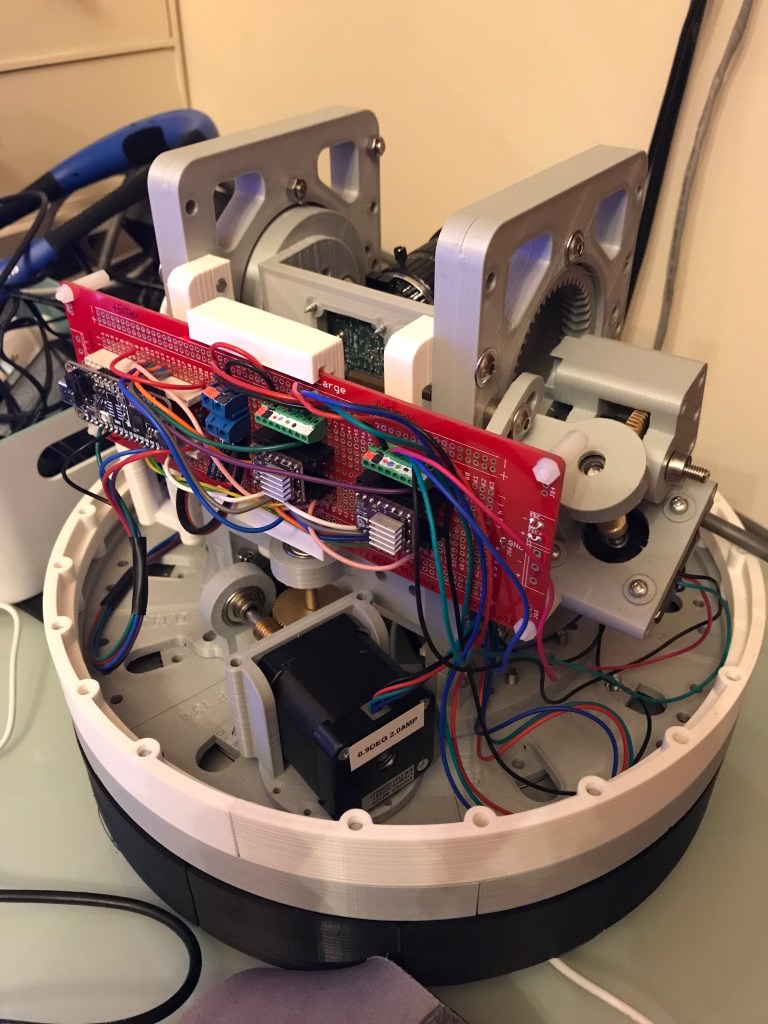

Smoother motor movement.

A whole bunch of ideas came from other builders, it became clear that microstepping is easy and safe to activate for most people. Microstepping makes movement slower, but smoother and quieter. It required some rethinking of the code on the microcontroller because microstepping generates a lot more motor pulses, a limitation with the clock in CircuitPython became apparent but is now resolved. There is also a ‘slew’ mode available in the latest package. This lets the telescope perform LARGE moves using full steps on the motor – noisy by fast. Then when it starts capturing the observation images it switches to microstepping.

Better microstepping support also means that you can build using the 200step stepper motors now. These are generally easier and cheaper to buy.

Easier configuration changes.

Pi-lomar’s configuration is generally held in the parameter file. You can make a lot of changes to the behaviour there. This latest release has moved even more of the configuration into this one file. However some changes can be quite complex to configure correctly. Therefore the latest software has added a few options to perform some common configuration changes directly from the menus. This ensures more consistent and reliable setup for a few camera options and also for configuring several of the microstepping related issues.

Aurora features.

After the spectacular Aurora displays earlier in the spring, I’ve added some experimental Aurora recording features to the software too. Obviously we now have to wait for some good Aurora displays to fully test this feature, but the basic concept seems to work OK. In Aurora mode the camera points to a likely direction for the Aurora and captures images as quickly as possible. It can also generate a simple KEOGRAPH of the aurora display which may be interesting to study sometimes.

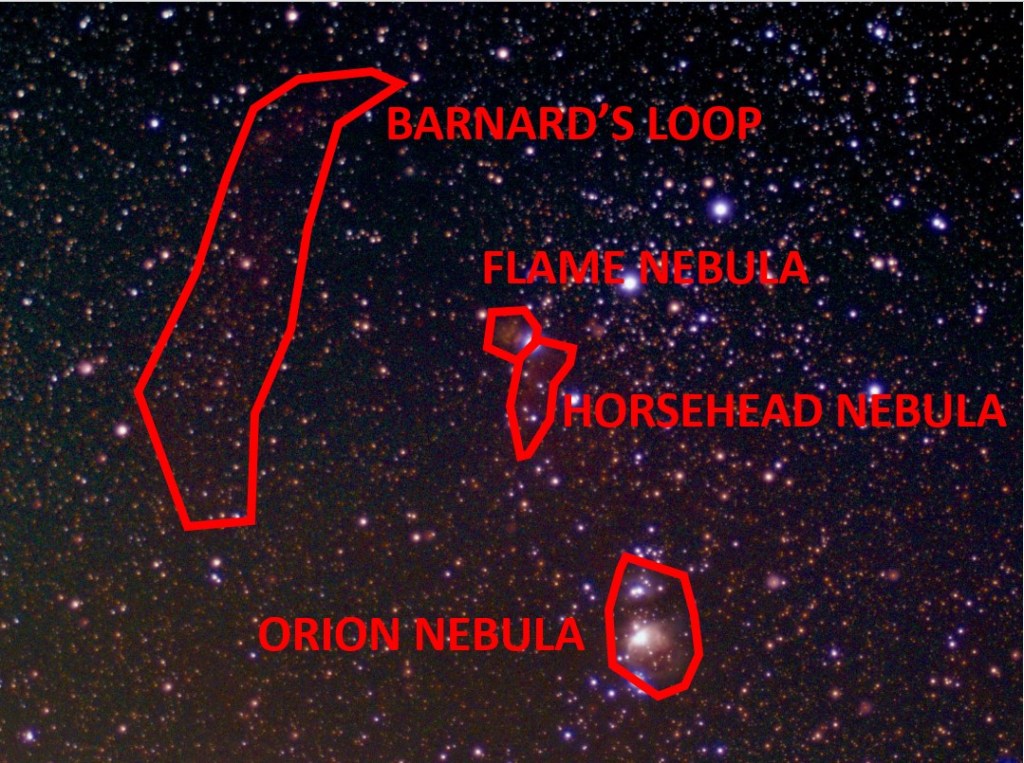

Observations

Well, summer is here now, and the skies are too light, too short and sadly still too cloudy. So no practical observations of anything new to show this time. All the project work has gone into this latest software development round instead.

So I’m now looking forward to slightly longer and darker nights coming in August and September, and hoping that the clouds go away.

What’s next?

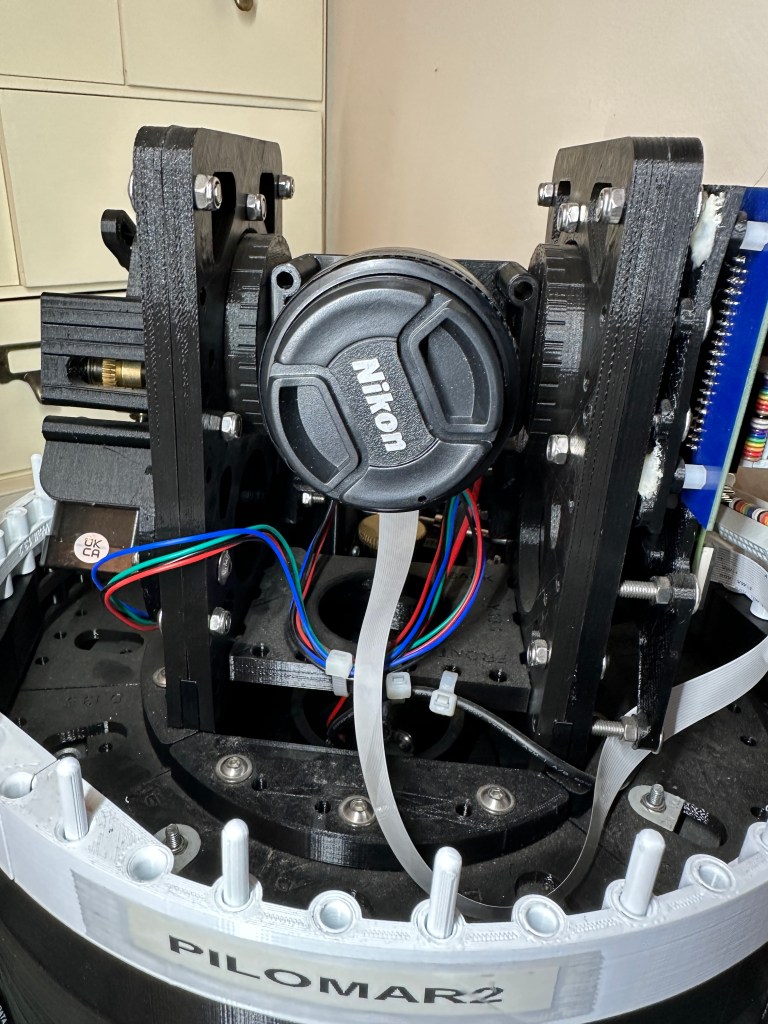

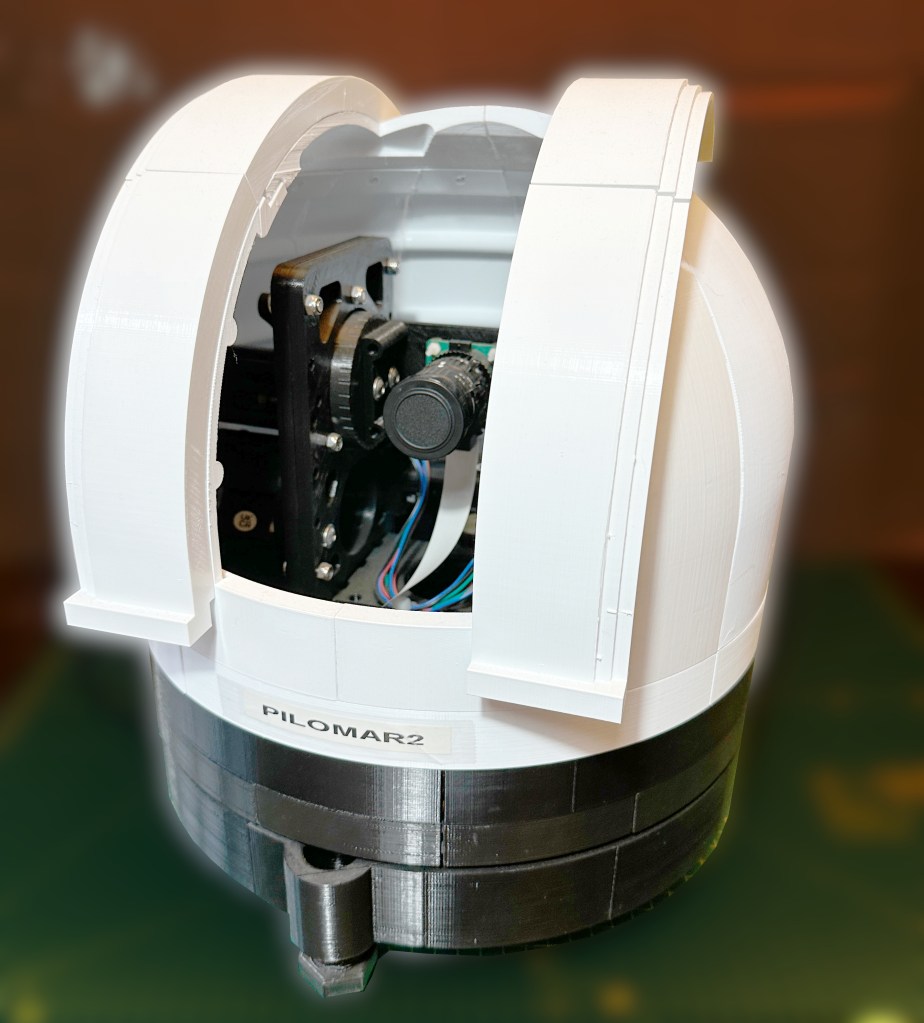

I’m currently exploring some modifications to the telescope design.

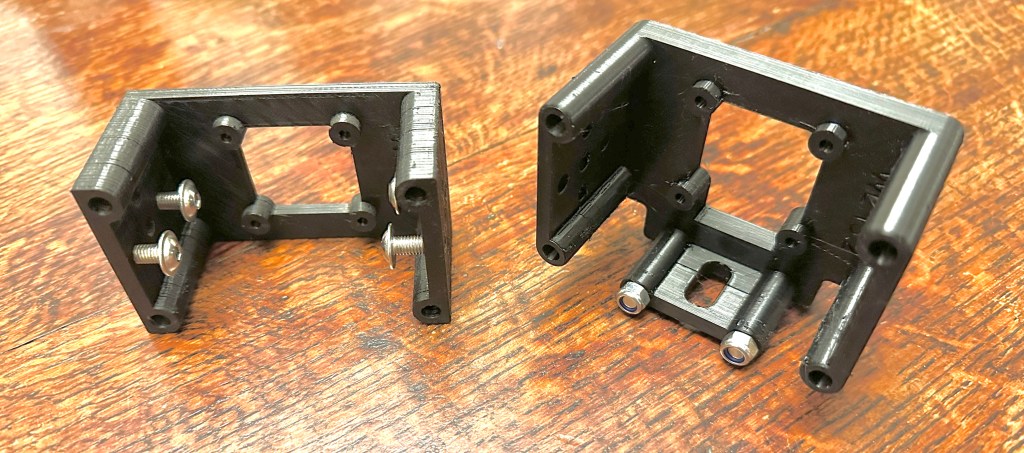

Now that the RPi5 is supported – it has TWO camera ports! So I would like to explore the idea of having two cameras mounted in the telescope. Ideally a 16mm lens dedicated to tracking, and then a 50mm higher quality lens dedicated to observation pictures. There is also some feedback from other builders which is re-opening the design of the camera tower and camera

cradle. I’m currently thinking to make a slightly wider camera tower to accommodate 2 cameras, and probably reorienting the sensors into portrait mode to improve access for focusing. It may make sense to improve the weatherproofing around the camera boards – as others have already done.

After a chat in the Discord group I’m also looking at adding a permanent ‘lens cap’ to the camera tower. This would sit below the horizontal position of the camera, so that the lens can be parked up against it when not in use. There are a

couple of advantages to this idea. (1) You don’t have to remember to remove or reinstall the lens cap. (2) If the cap is sufficiently dark the camera can take the ‘dark’ control images automatically at the end of each observation.

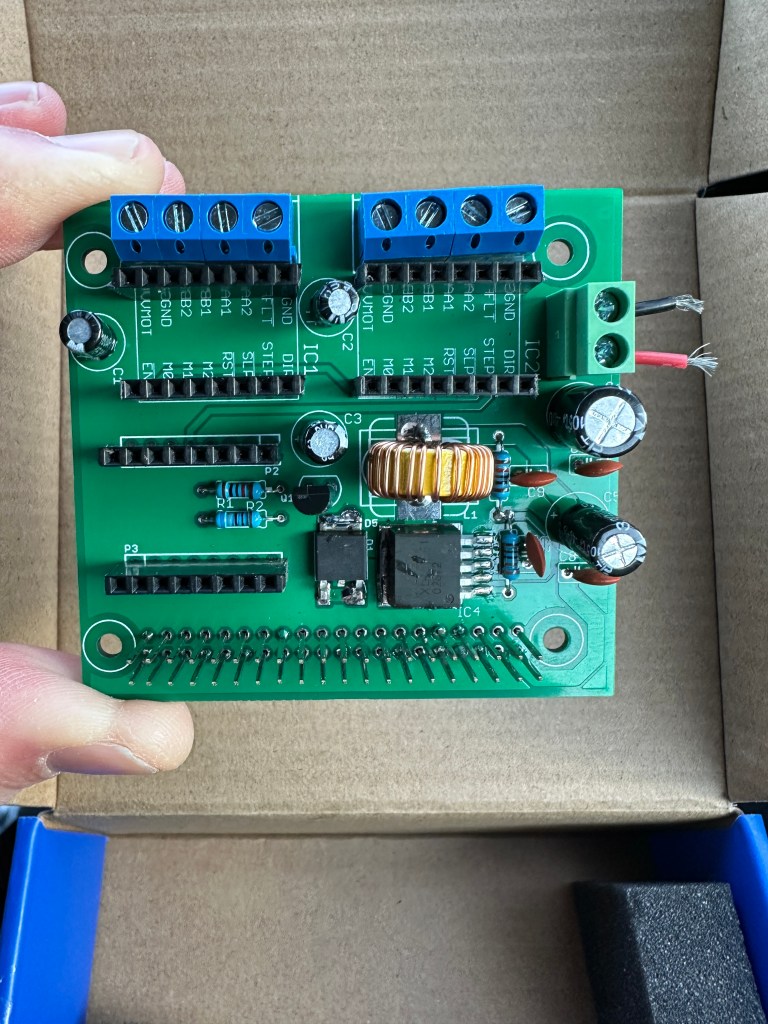

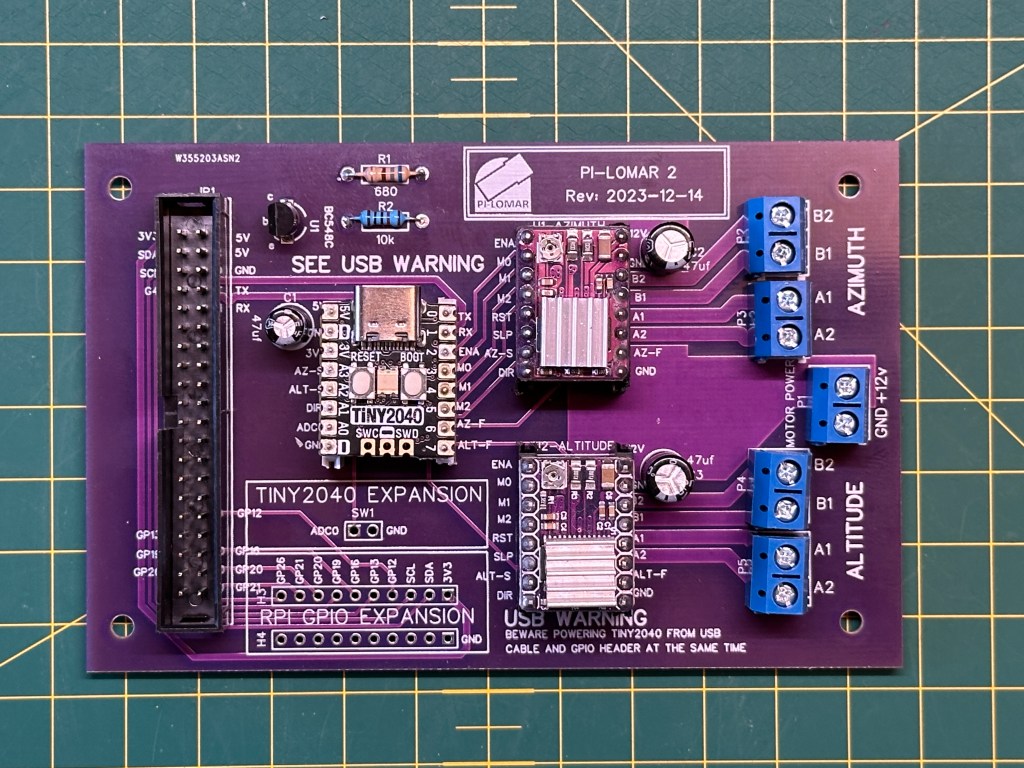

I have a redesign of the motorcontroller PCB nearly ready, with improved power performance for the microcontroller. There will probably be another couple of improvements made to it, and then I’ll try getting some samples printed up. I considered switching from the Tiny2040 microcontroller to something larger with more GPIO pins, but have decided to stick with the current setup. There seems to be a practical memory limit on the RP2040 chip in the microcontroller, it has around 200K of working memory available to it, and the current functionality consumes it all. I cannot even get the current code to run on CircuitPython 9.x yet, so it’s still limited to 7.2 and 8.2. It may be worth waiting to see if any 2nd generation microcontroller comes from RPi in the near future before finalising the design.